Chicago and Indianapolis – What’s the Connection?

Chicago and Indianapolis – What’s the Connection? features the work of faculty members at the Herron School of Art and Design in Indianapolis. The Herron School was originally part of the John Herron Art Institute, established in 1902 by the Art Association of Indianapolis. In 1967 the school functions of the Herron Art Institute were transferred to Indiana University. This exhibition explores common themes and concerns of contemporary artists working in Chicago and Indianapolis. Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago July 14 - August 16, 2017 opening reception: July 14, 2017 - 5:00 to 8:00pm

Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago July 14 - August 16, 2017

Chicago and Indianapolis - What's the Connection? a group exhibtion curated by Michael Robertson & Christopher Slapak Anila Quayyum Agha Ray Duffey Valerie Eickmeier Reagan Furqueron Marc Jacobson Melissa Parrott Quimby William Potter Andrew Winship July 14 - August 16, 2017

Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago July 14 - August 16, 2017

Chicago and Indianapolis - What's the Connection? a group exhibtion curated by Michael Robertson & Christopher Slapak Anila Quayyum Agha Ray Duffey Valerie Eickmeier Reagan Furqueron Marc Jacobson Melissa Parrott Quimby William Potter Andrew Winship July 14 - August 16, 2017

Zolla/Lieberman Gallery, Chicago July 14 - August 16, 2017

Chicago and Indianapolis - What's the Connection? a group exhibtion curated by Michael Robertson & Christopher Slapak Anila Quayyum Agha Ray Duffey Valerie Eickmeier Reagan Furqueron Marc Jacobson Melissa Parrott Quimby William Potter Andrew Winship July 14 - August 16, 2017

Gesture Control

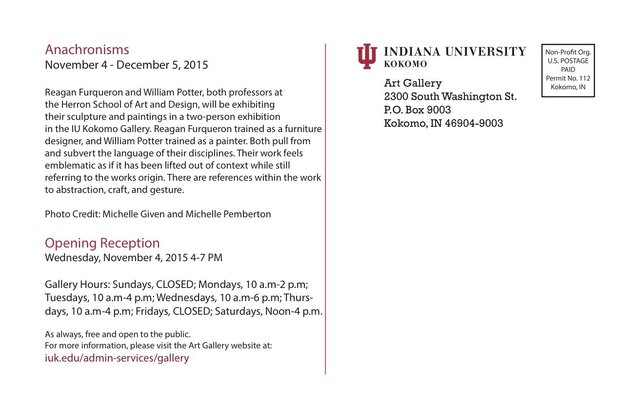

Anachronisms: Reagan Furqueron and William Potter

IU Kokomo Gallery

Anachronisms: Reagan Furqueron and William Potter

Installation View

Anachronisms: Reagan Furqueron and William Potter

Installation View

Anachronisms: Reagan Furqueron and William Potter

Installation View

Anachronisms: Reagan Furqueron and William Potter

Installation View

Anachronisms: Reagan Furqueron and William Potter

Installation View

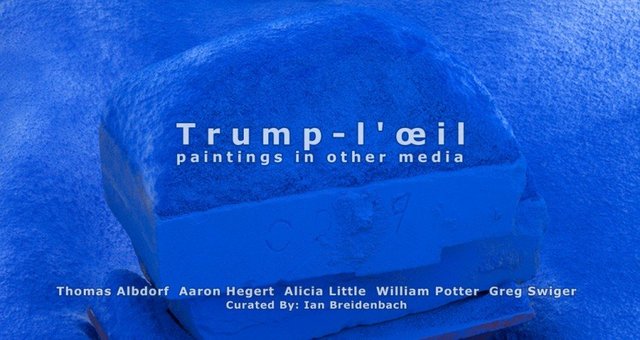

Trump-l'oeil

Blue House Gallery

Trump-l'oeil: Paintings in other media

Installation View

Trump-l'oeil: Paintings in other media

Installation View

Trump-l'oeil: Paintings in other media

Installation View

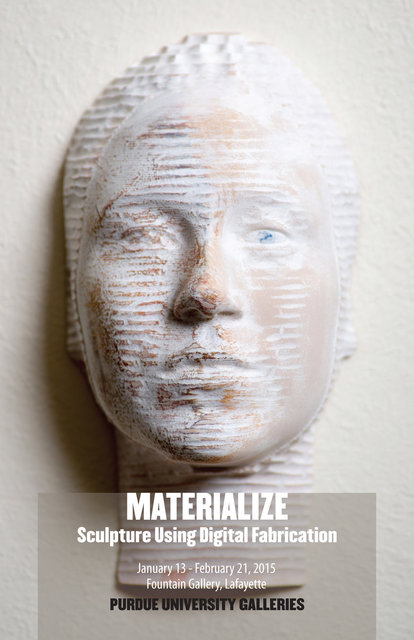

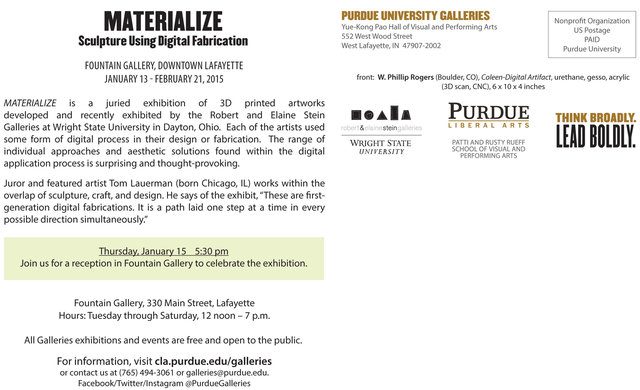

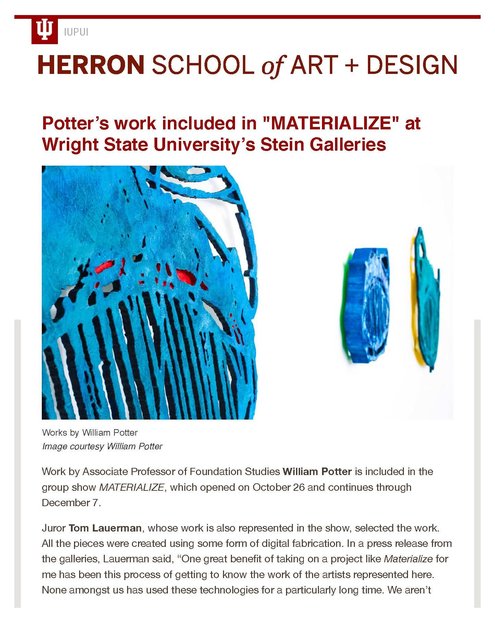

Materialize | Sculpture Using Digital Fabrication

Materialize - Juror’s Statement, Tom Lauerman What a great pleasure it is to have been asked to be the juror of Materialize, an exhibition exploring the potential for 3D printing and Digital Fabrication as vehicles for artistic exploration. 3D printing, having been invented just over 30 years ago - but only now nudging into the public consciousness, is having something of a moment. The technology (referred to alternatively as Rapid Prototyping, Additive Manufacturing, Desktop Manufacturing, or a host of others) is simple enough: An object is built, one layer at a time. Each layer is stacked upon the previous one until complete. Coil-built pottery works along the exact same principle. As it turns out, I’ve logged thousands of hours smushing clay around, via coil, slab, mold, or just plain old pinching between the fingers. I’ve likely logged as many hours designing objects with a computer interface, using various 3D Modeling or Computer Aided Drafting software applications. For many years these twin processes seemed likely to remain as two parallel pursuits - one virtual, one physical. Surprisingly, these paths crossed for me in 2008, the first time I 3D printed something - at great expense, with no direct contact with the machine actually doing the printing. The first object I printed was a highly detailed tile. I used it to generate a plaster mold, and shortly thereafter, an object made of clay. Right from the start I was absolutely floored by the potential represented in the combination of Digital Fabrication tools with established and experimental studio forming methods. The implications appear to be huge, for every material, at every scale. Technologically, little has changed for artists interested in this technology in the last decade. The Digital Fabrication equipment we use in 2014 is doing almost exactly what it did back in 2003. The difference is about access. Suddenly, the price of a 3D printer dropped to a couple of thousand dollars, then to several hundred, then to just a few hundred - assuming you might enjoy scavenging tiny little motors and springs and gears from cast-off electronic debris of years past. And it is only the tip of the iceberg for sure. If 3D printing might be compared to the rise of the home computer in the 1970’s or 1980’s we are perhaps only just now entering an era analogous to such mostly forgotten computers as the TRS-80, the Apple II, The Commodore 64. Mainstream acceptance of this technology lies ahead. A reliable 3D printer which “just works” is also still something we mostly have to imagine too. So the artists represented in this exhibition represent “Early Adopters”, those who have sought out a nascent technology in part because of the thrill of its new-ness, or in order to tap into it’s unusual capabilities. It is important to point this out now, because in a few years time, there may be nothing novel about using 3D printers as an artist. The technology may engender it’s own well-deserved backlash soon, as all of us get more than a little fatigued by the steady stream of sensational claims being made by the players in this emerging industry. But for the moment, let’s suspend judgement about the long-term impact of Digital Fabrication on Studio Art production as this technology begins to dovetail with traditional means of artistic production. For the moment, let’s appreciate that each of the artists in this exhibition went out of their way to meet this technology on it’s own terms, to explore it, to embed it within their ongoing bodies of work. Their reasons for doing so are likely varied. One might use the technology for practical reasons: to achieve a smoother finish perhaps. Or to achieve an almost perfect duplicate or “clone” of another form. To express form with a kind of mathematical clarity. In a few cases, these artists might have turned to these technologies to save time. Typically one discovers along the way that they have not only not saved time, but fallen deep into a technological rabbit hole which is at turns seductive or terrifying - but always massively time-consuming. Another reason to embrace Digital Fabrication could be that artists and designers raised as “digital natives” might actually be more comfortable generating form on-screen. These individuals might walk into a wood or metal shop and be intimidated or lost, but be right at home with the most complicated additive or subtractive or generative sculpting technique when it is expressed in backlit pixels. Perhaps, after years of creating images and experiences on screen, these young artists are eager to engage the physical world through touch, weight, materiality, and density. Maybe some of the artists in this exhibition arrived at these ways of working simply out of fascination with the technology and its potential. To work with Digital Fabrication in the early part of the 21st century is to be routinely amazed by the seemingly magical transition from code to form while being constantly reminded of the horrendous limitations inherent in the process. In this sense, designing an object on-screen is often bittersweet. The artist/designer has to reconcile some perfect on-screen image with the deeply imperfect means available for bringing it into the world. At present, 3D printing materials tend to be cheap plastics, or crumbly powders, of small size and great expense. How can an artist get around this limitation? One approach would be to disguise the material as something else - perhaps make it look like bronze or wood through an elaborate patination or faux-finish technique. For the most part I edited out this type of approach from Materialize. It is too easy of a solution to the problem I feel, and so you see very little on display here which is not what it appears to be in terms of materiality. Two other solutions to the problem of materiality presented themselves. The first solution involves artists with considerable skills in another medium/material. Many of the artists on view in Materialize have toiled in esoteric shops for years learning the particular nuances of specific tools and materials. For these artists, the solution was to hybridize their process. For example, a printed or CNC-milled form is turned into a mold, which is turned into an object of substantially more substance than we typically ascribe to plastics or foam. I want to point out to the casual observer that this process of material translation is complex, tedious, and often not well described in available literature. When we think of creativity in art we don’t immediately think of the ingenuity involved in the physical making process. I’m asking you, the viewer, to find and celebrate the ingenuity at work in the creation of many of these multi- and mixed-media works which began their lives on flickering screens. The second solution to the problem of materiality is to allow the work to be (as Apple’s Jonathan Ive once described a product) Unabashedly Plastic. Many of the objects here are just that, and wear their near-immateriality with pride. In this exhibition you can find objects whose textures are light, cheap, and, perhaps ironically, nearly indestructible. In some cases this unabashed plastic-ness allows the viewer to suddenly regard an artwork as not inherently valuable or particularly unique. Therefore, that object is highly reproducible and highly reconfigurable. Indeed, some of the objects in this exhibition can be freely downloaded and printed, by you, at your home, as open-source artworks. This gets into really unusual territory in a contemporary art world that can feel as if it is centered around the production and marketing of unique and scarce expression at unimaginable prices. In other examples on view here, materials are transformed via context, multiplication, or sheer labor. Artists working with electronics, microcontrollers, and interactivity will do astonishing things with this technology in coming years. Who is better positioned to take advantage of the unique characteristics of plastic? It’s disarming familiarity, its translucency, its tactile suppleness. No longer confined to “hacking” found objects, the artist manipulating circuitry can (again via open source innovations like Arduino) create an installation, an ecosystem, from scratch. Then they can multiply it, remix it, and share it digitally. The software artist Golan Levin recently stated that the teaching and sharing of open-source tools is “incompatible with the notion of the solitary genius”. Works in this exhibition include digital scans of past artworks, snippets of code from other contemporary works. Authorship is gently called into question. Perhaps collaboration is to be the ascendant mode of art-making in the coming decade. Hopefully these artist’s provocations will cause all of us to re-examine our own received notions of originality and creativity. One great benefit of taking on a project like Materialize for me has been this process of getting to know the work of the artists represented here. None amongst us has used these technologies for a particularly long time. We aren’t rebelling against a previous generation of Digital Fabrication artists whose work we feel constricted by. These are first-generation digital fabrications. It is a path laid one step at a time in every possible direction simultaneously. There will come a time in the post-digital-near-future wherein these pathways are more well worn, even worn-out. That time is not yet upon us, so let’s enjoy the very messy present of Digital Fabrication and imagine it in its best possible future guise. Tom Lauerman October 2014 State College, PA

Manifest Regional | OKI

Materialize: Wright State University

Materialize: Wright State University

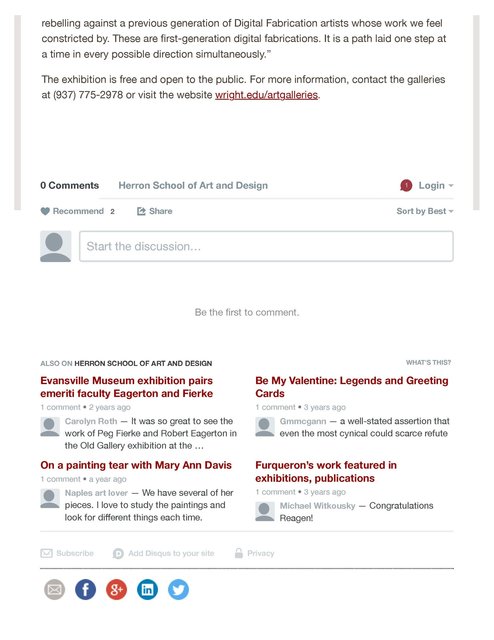

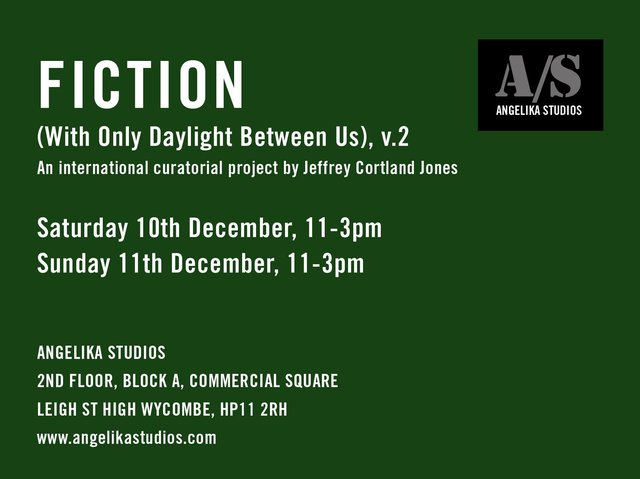

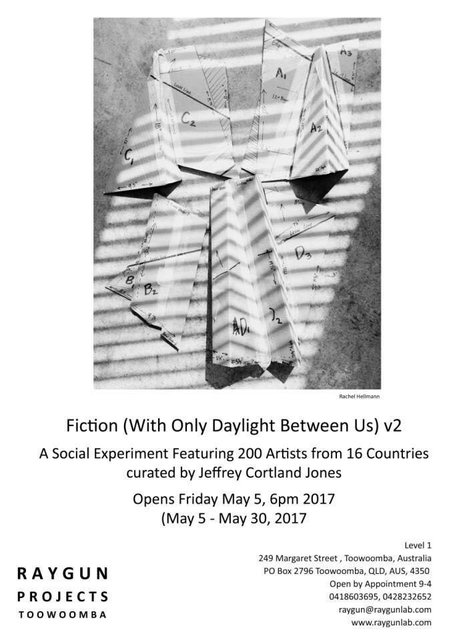

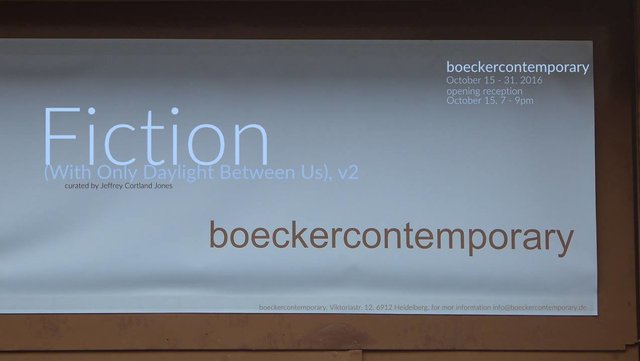

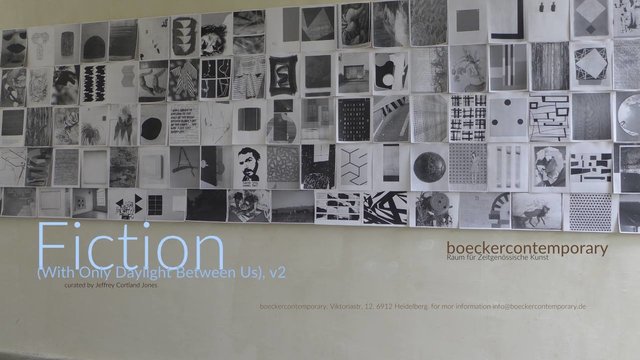

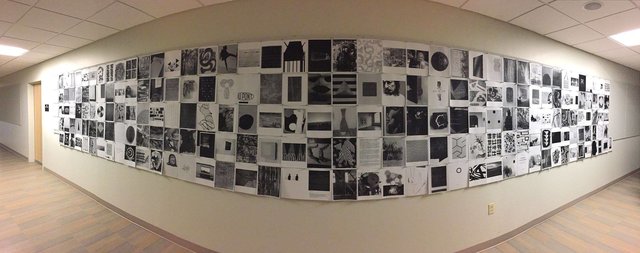

Fiction (with only daylight between us)

Neon Heater

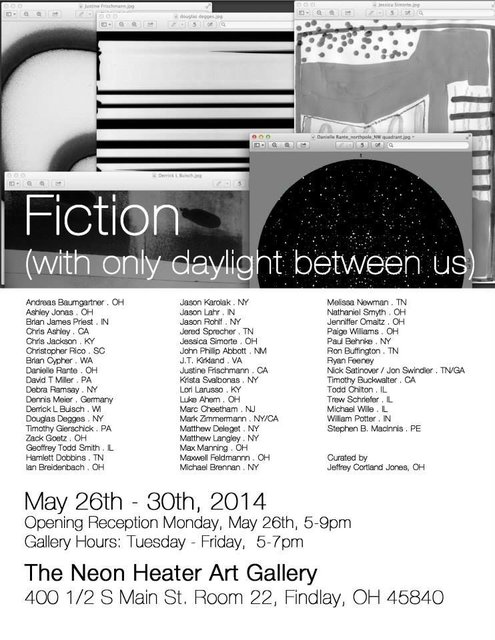

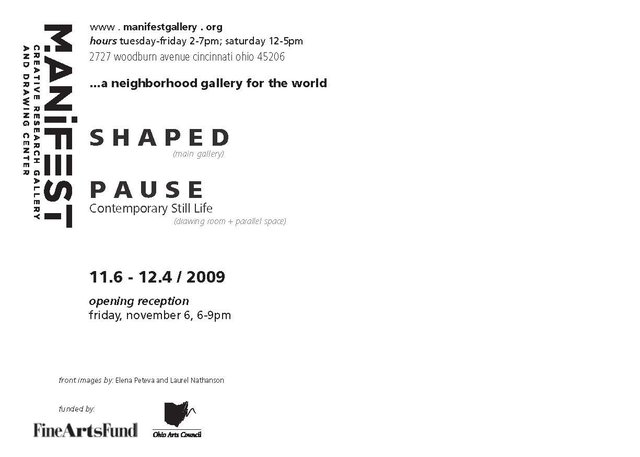

Shaped

Manifest Gallery

Shaped: Manifest Gallery

Installation View

Shaped: Manifest Gallery

Installation View

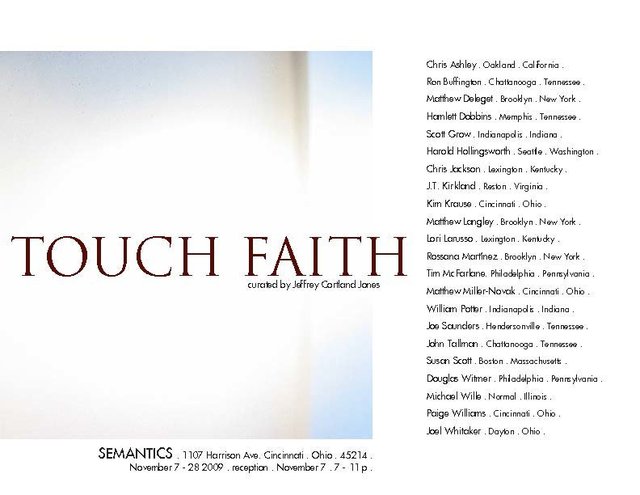

Touch Faith

Semantics Gallery

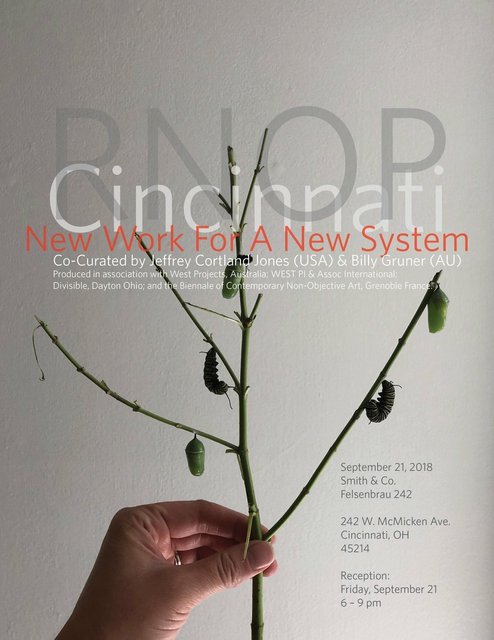

RNOP: Cincinnati

Manifest Regional | OKI

Manifest Regional | OKI

Manifest Regional | OKI

Manifest Regional | OKI

Manifest Regional | OKI

Manifest Regional | OKI